Finland

The data in this note reflect different sub-national geographic levels in OECD countries:

Regions are classified on two territorial levels reflecting the administrative organisation of countries: large regions (TL2) and small regions (TL3). Small regions are classified according to their access to metropolitan areas (Fadic et al. 2019).

Functional urban areas consist of cities – defined as densely populated local units with at least 50 000 inhabitants – and adjacent local units connected to the city (commuting zones) in terms of commuting flows (Dijkstra, Poelman, and Veneri 2019). Metropolitan areas refer to functional urban areas above 250 000 inhabitants.

In addition, some indicators use the degree of urbanisation classification (OECD et al. 2021), which defines three types of areas:

- Cities consist of contiguous grid cells that have a density of at least 1 500 inhabitants per km2 or are at least 50% built up, with a population of at least 50 000.

- Towns and semi-dense areas consist of contiguous grid cells with a density of at least 300 inhabitants per km2 and are at least 3% built up, with a total population of at least 5 000.

- Rural areas are cells that do not belong to a city or a town and semi-dense area. Most of these have a density below 300 inhabitants per km2.

Disclaimer: https://oecdcode.org/disclaimers/territories.html

Regional economic trends

Employment and unemployment rates in regions

In Finland, regional disparities in unemployment rates are moderate compared to other OECD countries. While in Southern Finland 8.1% of the working force was unemployed in 2022Q2, the share was 6.7% in Western Finland.

Meanwhile, the difference in employment rate between the regions with the highest (Helsinki-Uusimaa) and lowest (Eastern and Northern Finland) employment rates reached 10 percentage points in 2022.

Note: Harmonised employment and unemployment rates, aged 15 and over. The OECD median corresponds to the median employment rate in large regions.

Source: OECD (2022), “Short-term regional statistics”, OECD Regional Statistics (database)

The first year of COVID-19 on GDP per capita

The first year of COVID-19 resulted in a decrease in GDP per capita in all Finnish regions. Helsinki-Uusimaa, a region with a GDP per capita 29% above the national average (57 102 vs. 44 321 USD PPP), experienced the largest decrease in GDP among Finnish regions, of approximately -5%.

Note: GDP per capita is measured in constant prices and constant PPPs, reference year 2015. Constant prices are calculated using national deflators. The OECD median corresponds to the median decline in GDP per capita observed across OECD large regions over the period.

Source: OECD (2022), “Regional economy”, OECD Regional Statistics (database)

Trends in regional economic disparities in the last decade

Differences between Finnish regions in terms of GDP per capita have remained relatively stable over the past nine years, with the richest 20% of regions reporting a GDP per capita 1.6 times higher than the poorest 20% of regions.

Note: The GDP per capita of the top and bottom 20% regions are defined as those with the highest/lowest GDP per capita until the equivalent of 20% of the national population is reached. A ratio of 2 means the richest regions have a GDP per capita twice as large as the poorest regions. The indicator is calculated using large regions, except for Latvia and Estonia, where small regions are used instead. Irish GDP underwent an upwards revision in 2016. Care is advised in its interpretation.

Source: OECD (2022), “Regional economy”, OECD Regional Statistics (database)

Productivity trends in the last decade

Between 2010 and 2019, Southern Finland and Åland experienced the highest and lowest productivity growth in Finland, respectively. Southern Finland saw a labour productivity increase of 0.7% per year, below the OECD average of 0.9%1. During the same period, Åland experienced a decline in measured labour productivity, averaging -0.6% per year.

All Finnish regions experienced a decline in labour productivity between 2019 and 2020. Åland experienced the largest decline, with a drop of 14.2%

Note: Regional Gross Value Added (GVA) per worker, in USD, constant prices, constant PPP, base year 2015.

Source: OECD (2022), “Regional economy”, OECD Regional Statistics (database)

Well-being, liveability and inclusion in regions

Regional well-being

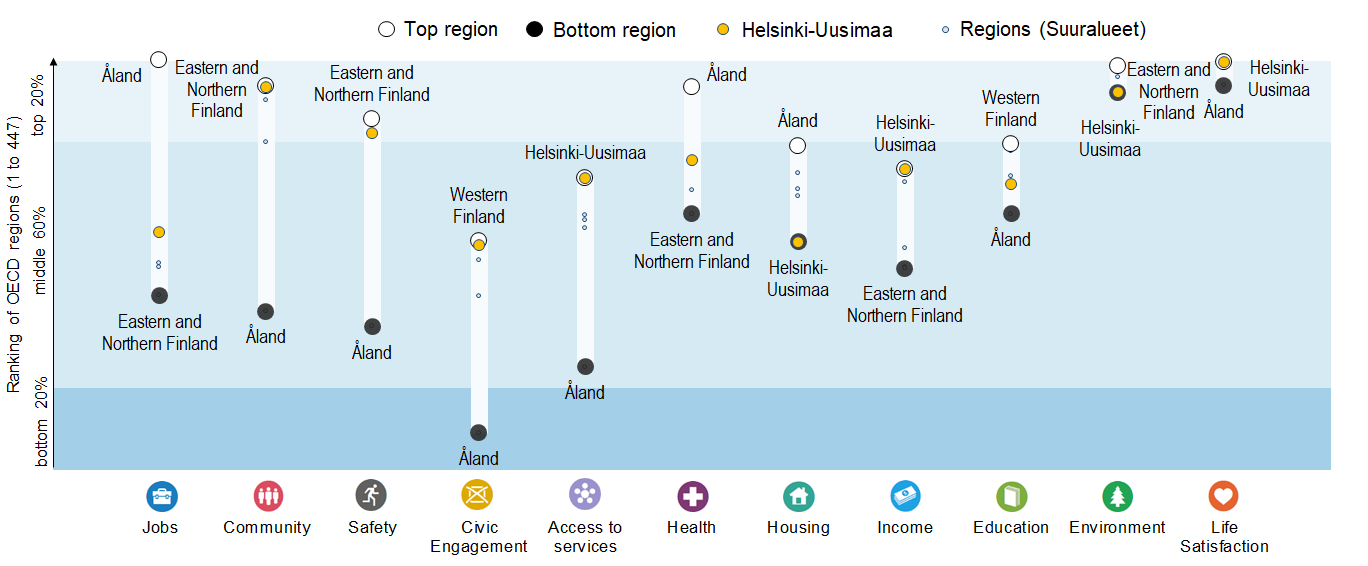

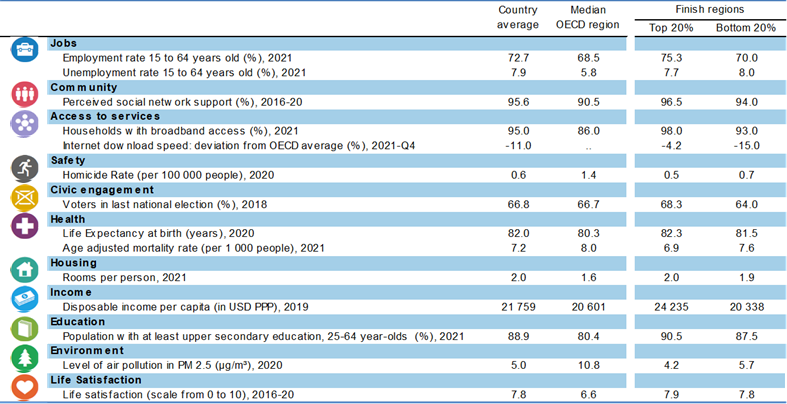

Finland faces stark regional disparities across six well-being dimensions, with the starkest disparities in terms of jobs, community and safety.

Note: Regional indices provide a first comparative glance of well-being in OECD regions. The figure shows the relative ranking of the regions with the best and worst outcomes in the eleven well-being dimensions, relative to all OECD regions. The eleven dimensions are ordered by decreasing regional disparities in the country. Each well-being dimension is measured by the indicators in the table below.

Relative to other OECD regions, Finland performs best in the environment and life satisfaction dimensions, with all Finnish regions lying in the top 20% of OECD regions.

The top 20% of Finnish regions rank above the OECD median region in 12 out of 14 well-being indicators, performing best in terms of reported life satisfaction.

Note: Regional well-being indices are affected by the availability and comparability of regional data across OECD countries. The indicators used to create the indices can therefore vary across OECD publications as new information becomes available. For more visuals, visit https://www.oecdregionalwellbeing.org.

The digital divide

Fixed Internet connections in Finnish cities and rural areas deliver speeds significantly slower than the OECD average (-1% and -27%, respectively). This gap (26 percentage points) is smaller than in most other OECD countries.

Note: Cities and rural areas are identified according to the degree of urbanisation (OECD et al. 2021). Internet speed measurements are based on speed tests performed by users around the globe via the Ookla Speedtest platform. As such, data may be subject to testing biases (e.g. fast connections being tested more frequently), or to strategic testing by ISPs in specific markets to boost averages. For a more comprehensive picture of Internet quality and connectivity across places, see OECD (2022), “Broadband networks of the future”.

Source: OECD calculations based on Speedtest by Ookla Global Fixed and Mobile Network Performance Maps for 2020Q4.

The average speed of fixed Internet connections is below the OECD average in all Finnish regions. Within the country, residents of Helsinki-Uusimaa, Southern Finland and Eastern and Northern Finland experience the fastest connections.

Relative poverty rates

In Finland, relative poverty rates2 range from 9% to 17% across regions. This 8 percentage point difference is less pronounced than the average difference observed across the 29 OECD countries with available data (16 percentage points), placing Finland among the five countries with the smallest regional disparities in the OECD.

Note: The OECD median gives the median relative poverty rate observed in a sample made of 326 large regions (from 28 countries), and 28 small regions (from Denmark, Lithuania and the Slovak Republic). Data corresponds to 2020 or the latest available year.

Demographic trends in regions and cities

Population projections by type of regions across OECD countries

Between 2020 and 2040, the population of Finland is expected to grow in metropolitan regions and decrease in other types of regions. Regions near a metropolitan area are expected to see the greatest change, with their population decreasing, on average, by 13 % over the next two decades.

Note: Lines represent the population projection in OECD countries per type of region (Fadic et al. 2019). Finland is highlighted in blue.

Dependency rate and proportion of the elderly

In the coming two decades, the share of the elderly population in Finland is expected to increase across all types of regions.

The elderly dependency rate3 in Finland is also higher than the OECD average (26.8 %) in most regions, ranging from 43.1% in Southern Finland to 27.1% in Helsinki-Uusimaa.

Population in cities

Between 2010 and 2022, 86% of cities in Finland experienced a rise in population. Population growth ranged from 0.0% per year in Lahti to 1.2% per year in Helsinki.

Note: Cities refer to functional urban areas (Dijkstra, Poelman, and Veneri 2019). The boundaries of functional urban areas correspond to the 2020 Urban Audit. Population counts for the functional urban area are aggregated from administrative, municipal-level, data.

Over the past decade, the population has grown the most in Finnish cities with more than 1.5 million inhabitants. Cities with 100 000 to 250 000 inhabitants have seen their population grow, on average, but to a lesser extent.

Environmental challenges in regions and cities

Greenhouse gas emissions in regions

Since 1990, production-based greenhouse gas emissions have decreased in most Finnish regions. Åland (1%) and Southern Finland (-19%) experienced the largest increase and decrease in emissions, respectively.

On average, Finnish regions decreased their emissions by 0.32% per year between 1990 and 2018. This is below the 1.93% yearly reduction rate needed to reach the EU target of a 55% reduction in emissions by 2030, with respect to 1990 levels.

Note: Bubbles are proportional to per capita greenhouse gas emissions, not to the overall level of greenhouse gas emissions in the region.

Source: OECD calculations, based on the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (European Commission. Joint Research Centre. 2019).

In 2018, greenhouse gas emissions per capita in Finland were largest in Southern Finland, Eastern and Northern Finland and Helsinki-Uusimaa. Power accounts for the largest share of greenhouse gas emissions in the three regions.

Note: Regions with low population counts may rank high in greenhouse gas emissions per capita while contributing relatively little to overall emissions in the country.

Urban heat island effect

In Finnish cities, the difference in temperature between cities and their surrounding areas (i.e. urban heat island intensity) reaches 3.7 degrees Celsius (°C). The largest effect is observed in Tampere and Jyvaskyla, two cities that are, on average, 4.4°C and 4.1°C warmer than their surrounding areas, respectively.

Note: The Urban Heat Island Intensity (UHI) index is defined as the difference in land surface temperature between built-up areas and non-built-up areas within functional urban areas. This index can be affected by the type of vegetation and climate in non-built-up areas.

Source: OECD calculations, based on land surface temperature data from NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) (Wan, Hook, and Hulley 2021a, 2021b)

References

Source of administrative boundaries: © OECD, © EuroGeographics, National Statistical Offices, © UN-FAO Global Administrative Unit Layers (GAUL)

Footnotes

International comparability in 2019 and 2020 is limited because of methodological differences in the calculation of employment counts during the height of the COVID-19 economic crisis.↩︎

The relative poverty rate gives the share of people – as a % of the regional population – with an income below the relative poverty line (60% of the national median income).↩︎

The elderly dependency rate compares the number of elderly people at an age when they are generally economically inactive (i.e. aged 65 and over), to the number of people of working age (i.e. 15-64 years old).↩︎